By Michelle Tabart

I was recently out at dinner with a friend who is trying to launch an electric motorcycle startup in Australia. We talked about the potential of using sensors for people to locate available bikes, parking spots and charging stations through their smartphone in real time.

The next day, I was in a client meeting talking about fintech and how sensors, wifi and connected devices will open the door to more responsive payments solutions.

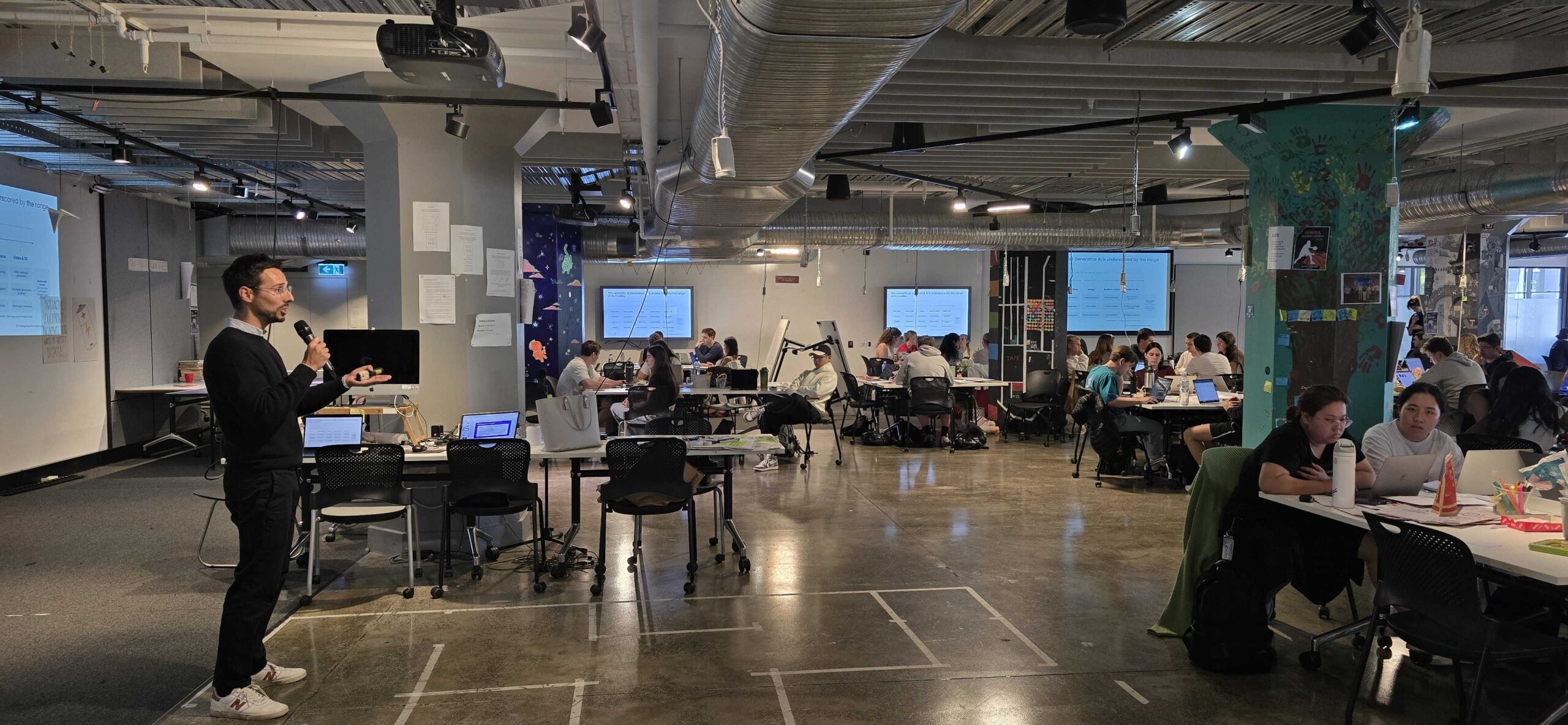

That same week, I went to an event on “democratising design” at the University of Sydney – which discussed the lack of open data or data freely availiable without restructions from copyright, patents or mechanisms of control available for citizen use about our cities. Open data is the idea that some data should be freely available use and republish without restrictions from copyright, patents or other mechanisms of control. The theme of my week seemed to be an issue that was topical for my friends, my work and the academic community: smart cities.

“Smart cities are “smart” because they use information communication technologies (ICT) to collect data that informs how we should improve our cities’ natural and built environments.”

On Twitter, Linkedin and other social forums there are passionate discussions about smart cities and their place in our society. But this community is divided into two schools of thought:

Proponents say that the outcomes will improve liveability, efficiency, job growth, productivity and citizen engagement. It’s a conversation at the local, state and national level that everyone can be a part of – which is scarce in the current innovation conversation.

Opponents argue that technology “giants” and government agencies are making decisions about smart cities without including their smart citizens. That the conversation is not open but already decided by those aiming to make money and improve their political score.

So what are the arguments for and against the “bottom up” (citizen led) and “top down” (government and technology led) deployment models?

Smart cities from the top down

From a corporate perspective, the Australian market opportunities for companies selling technology to cities is approximately $20 billion. Many large vendors are actively working with government agencies to identify areas of use for software and hardware products that create connectivity between our cities and our devices.

A few examples at the state level show that early stage smart cities’ programs are based on implementing sensors or information communication technologies (ICT) that collect data about roads, rubbish and lighting.

But, it’s not just the tech giants

There’s my electric motorcycle friend who is capitalising on the smart cities revolution through his startup. A few other examples of startups in the smart cities/internet of things (IoT) space are Spaceconnect, a startup that uses sensors for property managers to identify unused space and Wattcost, a startup that uses sensors to measure electricity usage and provide intelligent updates about how to reduce electricity bills. The growth of this industry will see many new businesses flourish and jobs created in the innovation nation.

Nonetheless, a key problem is that we are betting on smart technologies, not smart citizens.

The smart cities plan released by the federal government earlier this year has three pillars: smart investment, smart policy and smart technology. These pillars aim to create a more connected city that will help solve problems of rapid urbanization of data analysis. However, citizens are not considered a pillar but referenced as integral to the development and success of smart cities:

“If our cities are to continue to meet their residents’ needs, it is essential for people to engage and participate in planning and policy decisions that have an impact on their lives.”

This human-centred rhetoric is common across government smart cities plans globally. However, the three pillars of the federal government’s smart cities plan and the government’s receptivity to smart cities initiatives reflect that the focus is on technology and investment first with “citizen centricity” as a secondary concept.

This technology and investment-led approach is evident in several Australian smart cities projects which are using “personas” to develop solutions. The problem with this approach is that, personas are conceptualisations of people, not real people. Personas can’t actually test/trial products and services to ensure product/market fit before the government invests in these products. As a result, many smart cities projects are “verifying” potential solutions prescribed by the technology industry with conceptualisations of people rather than actual people.

Smart cities from the bottom up

One of the key grievances from the opponents of current smart cities initiatives is the lack of open data provided by the government to citizens. For smart cities, open data is proposed as the best way to give power back to the public to enable change in our cities. The proponents of open data encourage citizens to connect with data and form their own approaches and views on how to make cities “smart” without the influence of those trying to implement mechanisms of control or aiming to profit from the smart cities revolution.

A current example in Melbourne is the use of in-ground sensors to record parking times and then alert parking officers in the area who then generate infringements to drivers who breech their allotted period. The citizen response to this initiative has been overwhelmingly negative and seen as a “money grab” initiative. From the smart cities perspective, the core complaint is that the government should provide data from in-ground sensors that record parking times to allow public-generated solutions to parking challenges that would help decrease the number of people receiving “revenue-generating” traffic infringements. Clearly, the mechanism of controls used to deprive citizen access to this data is a catalyst for citizen-led solutions.

Yet, this argument also generates a division in two ways. Firstly, the bottom up debate engenders public disengagement with government and advocates an individualised approach to societal needs. While everyone may not agree this is a bad thing, if we are to create a smart city, should we do this with the intention of excluding government institutions? Secondly, citizen-led solutions fail to recognise the advantages of industry influence and knowledge, and marginalises corporations and their ability to provide valid contributions in this space.

Democratising the smart cities debate

The Australian take on a “smart” city has broadly been about instrumentation – the capacity to connect things. But what we’ve failed to do is connect with each other and break down the cultural barriers between government, industry and citizens. To democratise this debate we need to get past the rhetoric of “vendor/government” partnerships with a customer lens and citizen-led innovation that marginalizes government and private support.

Instead, we need to create initiatives that bring all parties to the table and bridge the common disconnect between technology and government, government and people, and people and technology.

“To create a truly “smart” city we need democracy, not division”

At The Strategy Group, we use leading innovation methodologies including Open and Lean Innovation and our tailored Design Thinking methodology to bridge this disconnect. To learn more about how we can help you do this contact me on michelle@thestrategygroup.com.au