The level of disruption is growing worldwide, and so is the need for innovation and creative thinking, along with that growth has been a wealth of problems with innovation approaches. Most smart companies are seriously focussed on building their innovation capability, and our focus on Design Thinking, Lean Startup and Open Innovation at The Strategy Group is exactly where the smartest of the smart are heading.

But it is not all smooth sailing, and our experience over the many years we have been immersed in the innovation space is that there are traps for the unwary, so called ‘innovation problems’. So, it was very interesting to read the HBR blog post from Innosight, the firm cofounded by Clayton Christensen, on the six most common mistakes companies make around innovation acceleration.

Asking employees to generate ideas without creating mechanisms to do something with them. Executives often get fooled by inspiring stories of engineers at companies like 3M or Google coming up with gems of ideas in the 15-20% of their time they allocate to side projects. If your organization does indeed have mechanisms to take idea fragments, process them, and turn them into fully fleshed out innovations, by all means open up the idea spigot. Otherwise, all you create is a long list of ideas that never go anywhere, and substantial organizational cynicism. This doesn’t necessarily mean setting up a department, but at the very least develop a set of criteria by which to judge ideas and have suggestions for how the best ideas can be acted on. Setting up an ideation platform may help avoid problems with innovation around useless ideas.

Pushing for answers without defining problems worth solving. We define innovation as something different that creates value. You only create value if you solve a problem that matters. Executives often think that the best way to spur innovation is to remove constraints, to let hundreds or thousands of flowers bloom. Overly fragmented efforts result in nothing more than a lot of undernourished flowers. Constraints and creativity are surprisingly close friends. Problems can range from entering new markets to addressing everyday concerns such as low employee engagement. Whatever they are, the more specific, the better. Without problems for innovation to solve, the innovation itself may become a problem.

Urging risk-taking while punishing commercial failure. “If I find 10,000 ways something won’t work, I haven’t failed,” Edison once said. “I am not discouraged, because every wrong attempt discarded is often a step forward.” Indeed, the academic literature suggests that almost every commercial success had a failure somewhere in its lineage. But inside most companies, working on something that “fails” commercially carries significant stigma, if not outright career risk. It’s no surprise that people play it safe! That’s not to say that companies should encourage failure. When people do something stupid, or they are sloppy, or they screw up something that has dramatic repercussions on the business, they should absolutely be held accountable (can you imagine a heart surgeon talking proudly about the patients he or she killed?). The trick is simply recognizing that in the early stages of innovation what at first appears to be failure is anything but.

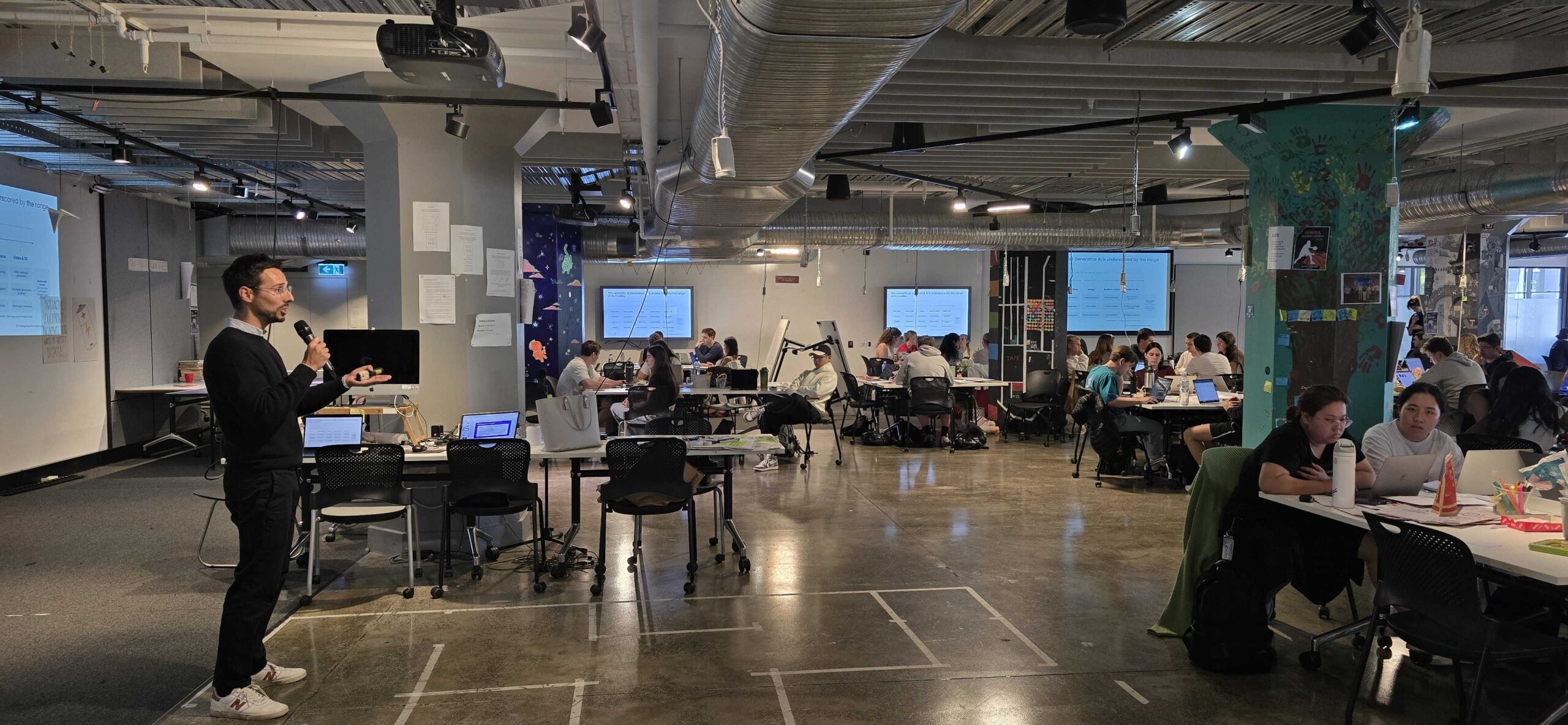

Expecting experiments without providing access to a well-stocked laboratory. It is increasingly well-understood that innovation success traces back to disciplined experimentation. Leaders transfixed with The Lean Startup or related books often urge their teams to develop minimum viable products or find other ways to rapidly prototype ideas. Indeed, finding smart ways to test is critical to innovation success, and this discipline goes well beyond prototypes. Consider what allowed the Wright brothers to successfully create a machine that allowed humans to fly. While most would-be aviators spent years building prototypes of their ideas, and then risked life and limb testing them, the Wright brothers flew kites and built wind tunnels. If your innovators don’t have the materials to build kites, or the space to fly them – or if they need to get 12 approvals to do so – don’t expect to see much experimentation.

Pleading for breakthrough impact without allocating A-team resources. Far too many companies create what you might call Potemkin portfolios. Just like the Russian prince Grigory Potemkin impressed Catherine the Great with villages that were nothing more than facades, companies build beautiful ideas on paper without considering the resources to turn them into reality. Innovation is hard work. The vast majority of startup companies fail, and that’s with tireless dedication from a team that has nothing to lose. If you don’t dedicate the right resources to your best ideas, you are consigning them to failure.

Demanding disruptive ideas, without ring-fencing resources for them. The essence of Clayton Christensen’s famous Innovator’s Dilemma is that companies privilege investments to sustain today’s business over those that have the potential to create tomorrow’s business. Along some dimensions, this is quite rational. After all, a dollar invested in the existing business produces a measurable, near-term return, whereas a dollar invested in a non-existent business promising ethereal returns at a difficult-to-pin down future date. Of course, over the long-run that disruptive investment might be a better proposition, but if the company hasn’t set aside resources specifically to drive disruption, the short-term will always win and issues with your innovation approach will rise quickly.